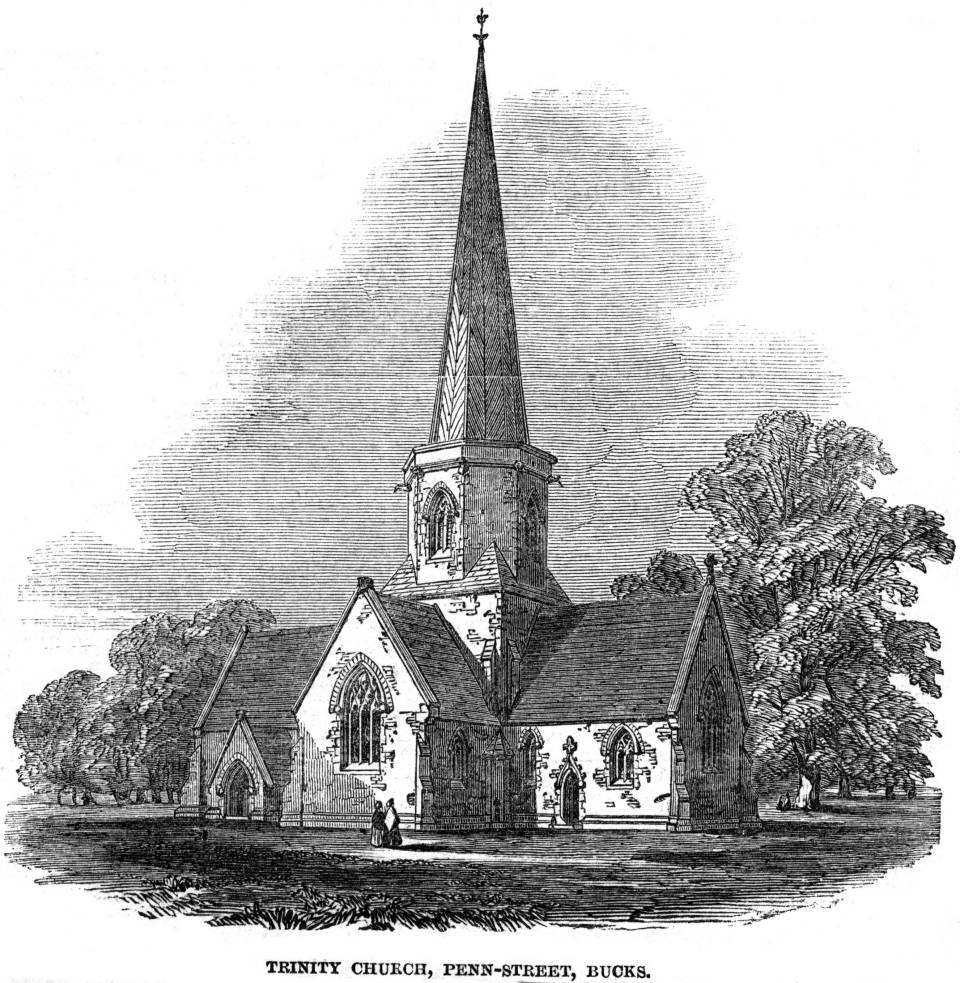

The following is a contemporary description of the consecration of a new church at Penn Street, in 1849, named Holy Trinity, one supposes, after the mother church of Penn.

This new edifice has just been completed at Penn-Street, a hamlet of the parish of Penn, situate about midway between Beaconsfield and Amersham, and not far from Wycombe, in the most picturesque portion of the county of Buckingham. The population is much scattered and the majority residing at a long distance from the parish church of Penn, have been almost destitute of the means of attending a place of public worship. The parish is owned by Earl Howe, whom this spiritual destitution induced, about two years since, to project the erection and endowment of a Church for the district, which has just been accomplished, at a cost approaching £10,000. Such munificence it is extremely gratifying to commemorate in our Journal.

This new edifice has just been completed at Penn-Street, a hamlet of the parish of Penn, situate about midway between Beaconsfield and Amersham, and not far from Wycombe, in the most picturesque portion of the county of Buckingham. The population is much scattered and the majority residing at a long distance from the parish church of Penn, have been almost destitute of the means of attending a place of public worship. The parish is owned by Earl Howe, whom this spiritual destitution induced, about two years since, to project the erection and endowment of a Church for the district, which has just been accomplished, at a cost approaching £10,000. Such munificence it is extremely gratifying to commemorate in our Journal.

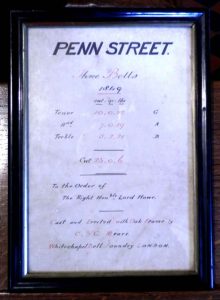

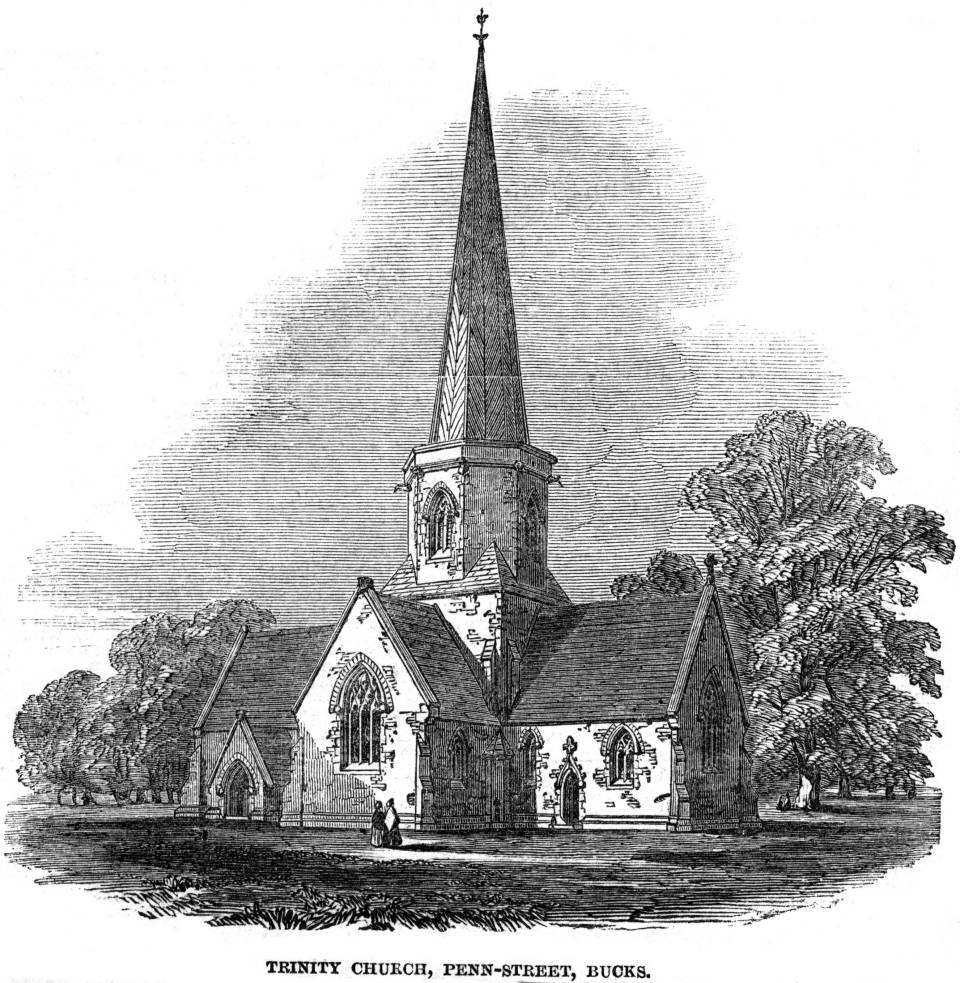

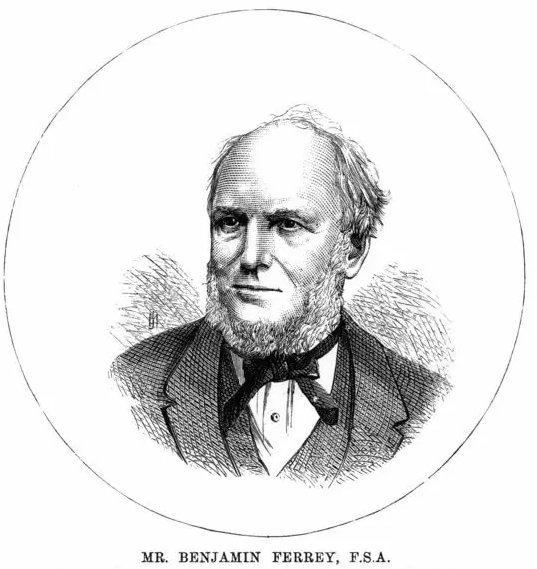

The site now occupied by the Church but a few months since was covered with timber, forming part of Penn-common Wood, and covering nearly 1000 acres. The design adopted by the architect (Mr Benjamin Ferrey) is the decorated style of the 14th century. The Church is cruciform in plan, and is calculated to afford accommodation to more than 400 persons. The whole interior is paved with encaustic tiles. The roof and fittings are of stained deal and the stained glass altar window was presented by her Majesty the Queen Dowager. The Church, from east to west, is about 150 feet long by thirty wide, and its height to the summit of the steeple is 140 feet. The whole structure has been completed within two years, and it is worthy to record that in its erection none but the tradesmen and tenants of the noble founder have been employed.

The consecration of the building took place last week, the Bishop of Oxford performing the interesting ceremony, in the presence of a vast concourse of spectators, attracted from the surrounding districts.

Among the leading personages present were Viscount and Viscountess Curzon, Lord and Lady Radstock and the Hon. Misses Waldegrave, Lord Boston and the Hon. Misses Ipley, Mr and Mrs Tyrwhitt Drake, Mr Bracebridge, Miss Norbury, and most of the influential families in the neighbourhood, and a large assemblage of clergy from the adjoining parishes. The road from the Manor-House to the church was very tastefully decorated with triumphal arches, formed of evergreens, and decorated with complimentary inscriptions, among which were – “In grateful esteem of Earl Howe”, “God bless the house of Curzon”, &c. The approaches to the Church, and the entrance to the churchyard were also spanned by evergreen arches, bearing appropriate Scripture texts.

The Lord Bishop was assisted by the Rev J Knollis, the Vicar of Penn, and the Rev E Bickersteth, the incumbent minister of the Church.

Near to the Church stands a very remarkable and picturesque tree, known as the “Queen’s Beech”, from the fact of her Majesty the Queen Dowager having, some years since, when on a visit at Penn, honoured with her presence a rustic entertainment given to the poor of the district, under the shadow of its branches, by Earl Howe.[]

The Need for a New Church

It is a little difficult to accept the argument that a new church was needed simply because the inhabitants of Penn Street had too far to go to Penn church. It is, after all, only some 2 miles. No mention is made of restricted space in Penn church and it would seem more likely that other factors were at work. A combination, perhaps, of the dreariness of Mr Knollis’ services, with what a Victorian eye would have seen as the impossibly out-of-date furnishings of his ancient church, the exterior completely covered with unattractive rendering, and with little prospect of any immediate change. Victorians did not generally see old buildings as we do today. Our desirable old brick and flint cottages were commonly described as “wretched” or “inferior” and Earl Howe may well have wanted to have an impressive and brand new church to show off to his Royal friends and other important personages. It is indeed a very splendid and expensive church for a small country parish. He may also have wanted to produce an attractive alternative to the Methodist chapels that were taking away so many Anglicans. The new church was built on common land, part of Wycombe Heath, which was not yet enclosed.

The New Boundaries

The new ecclesiastical boundaries for Penn Street included some 250 of Penn’s 1050 parishioners, as well as taking nearly 600 from Holmer Green and Beamond End, in Little Missenden, and a small part of Amersham parish.[] Thus both the reduced Penn & new Penn Street parishes were of almost the same size, with about 800 parishioners each.[] Earl Howe had no difficulty in arranging this, because he was of course, as his successor still is, the lay rector of both Penn and Little Missenden. Many of the Howe family have since been buried at Penn Street.

Parsonage and School

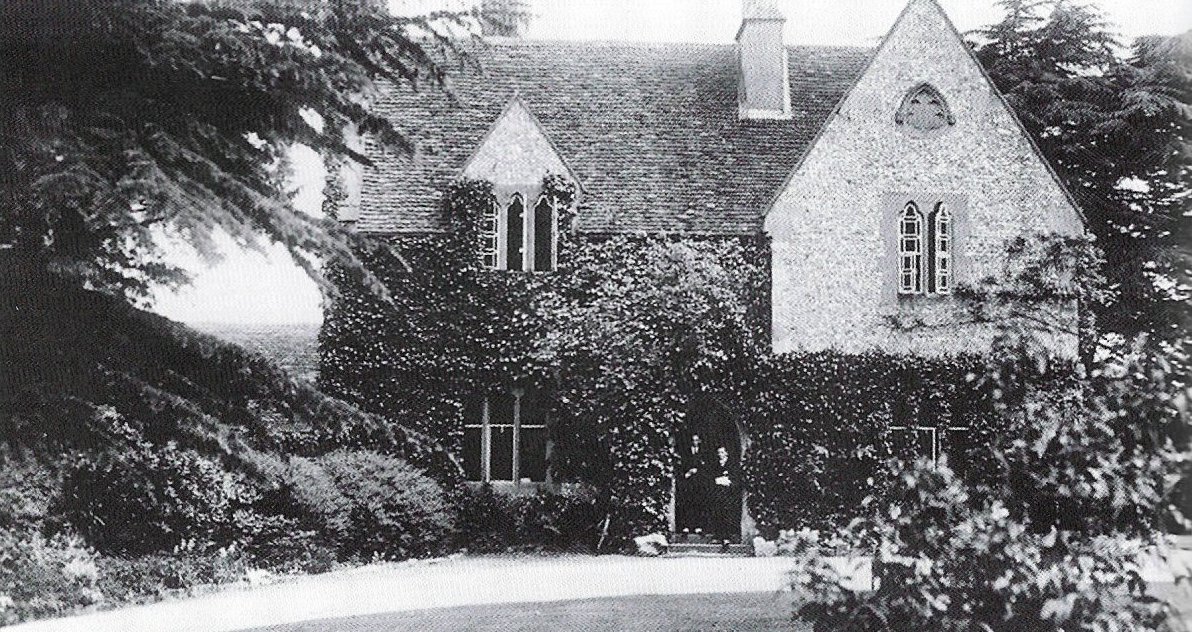

A very fine Parsonage House was built, at the same time, to match the splendid new church, and both together cost about £7000. In addition, Earl Howe endowed the living with income from rents of £143 p.a. The first vicar was Edward Bickersteth. He was succeeded, in 1853, by Alfred Butler. A school was built in 1850.[]

Charles Garland, Methodist and Church Builder

A most interesting family tradition is reported in The Methodist Recorder of 13 August 1936, about Charles Garland of Penn, which gives us a marvellous flavour of the period, and seems worth repeating in full, despite its length.[] The writer, a Methodist himself, describes it as, “the great story of what God wrought through one sermon”.

The sermon was heard by Mrs Garland, the wife of Charles Garland, of Penn. I do not know exactly what year it was, but at Windsor Mrs Garland heard Dr Adam Clarke (a Methodist theologian; died 1832). The discourse made such an impression upon her that she was led to see her trust must be not in the Church or its sacraments, but in the living Christ. She went home to Penn the next day and told her husband how her heart had been warmed. He was soon led into the same happy experience. They withdrew from the parish Church and joined a small company of Methodists, some of whom had been converted under the preaching of John Wesley during his visits to the neighbouring town of High “Wycombe.

Then the blow fell. Mr Garland was employed by Lord Curzon Howe, son of the famous admiral who is buried in Westminster Abbey. Lord Howe’s steward sent for Garland. “Now, my man,” he said curtly, ‘you can make your choice. You give up Methodism and return to worship at the parish Church, or you are dismissed from your work on the estate.” Garland made the reply you would expect from him: “I have made my choice, I am going to remain a Methodist. My conscience will not allow me to obey your order.” “Well,” said the unjust steward, “you can please yourself. I’ll give you a week to think it over. Lord Howe will not allow dissenters to work for him. You have been brought up in the Church. For some years your uncle was our vicar. There’s no reason whatever why you should become a Methodist.” Garland stood firm. He told the steward that he wanted no time for reflection and he would not give up his fellowship with the little Methodist society. In the following week the steward asked him to make up his accounts, and he was paid off. For several years his sole occupation had been that of estate builder to Lord Howe, the position having been held by his family for generations. The Penn Methodists needed a bold leader, and were greatly helped by the membership of Mr and Mrs Garland. The cause began to prosper. But not so the worldly affairs of the good man. About three years later Mr Garland told his wife she need not lock the cash box as it was empty. He was both workless and penniless. These were hard times. There was war with France. Food was scarce and dear, and it was almost impossible to obtain work apart from military service. Taking his long carpenter’s pencil from his pocket, Charles Garland balanced it up and down on his forefinger, saying to his family, “To-day is the parting of the ways; we shall either go up or down.” “It will be up!’ cried his good wife. They knelt down for their usual family prayer. The reading of a Psalm – “God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in time of trouble” – was interrupted by a loud knock on the door. A messenger from Lord Howe had come with a letter. His lordship had been serving his country abroad for three years and had unexpectedly arrived home. He wanted to see Mr Garland at once. Charles set off for Penn House, and as he walked through the woods the words kept coming into his mind – “We are at the parting of the ways; we shall either go up or down today. ”

Arriving at Penn House, he found Lord Howe waiting for him in the library. “Now, Garland, ” said his lordship, after referring to an anonymous letter he had received, “what is all this about? I had no idea you had been dismissed from the estate and were in great distress. What happened?” “I think, my lord” said Garland, quietly, “it would be better if you put that question to your steward.” “Certainly, I will see him today;,” said Lord Howe. “Come here again tomorrow and we’ll put matters right.” That same afternoon the steward was shown the anonymous letter and was asked for an explanation. “It is true, ” he said, “that I dismissed Mr Garland because he became a Methodist and refused to return to the Church. I thought it was the only way to bring him to his senses.” “I should-like to know,” cried Lord Howe angrily, “what a man’s conscience concerning his religion has to do with you if he is a good employee. In my name you have brutally persecuted a man whom I respect. There is only one course for me to take. You are my steward no longer. Hand over all your papers. I shall allow you a small pension, but if you want it to continue keep out of my sight for I never want to see you again!” The discomfited steward slunk away, speechless.

Later, Lord Howe expressed his regret to Mr Garland. “I want a steward,” he said, “and you shall be the man, for if you are so loyal to your God you are sure to serve me faithfully in earthly things.” This proved true. Garland exercised a great influence in the locality. The vicar of the parish was among those who were led to a deeper experience of evangelical truth. Lord Howe and his family became deeply interested in the earnest efforts of the Methodist. A Chapel was built during the later years of Mr Garland’s stewardship.[] Somewhere about 1849, his employer instructed him to build Penn Street Parish Church. Penn Street is a small village, about two and a half miles from Penn. The Church faces the entrance gates to Penn House, a mansion of brick in a small park of thirty-two acres, the ancestral abode of the Howe family. You could not imagine a more picturesque or a more beautifully situated sanctuary. It is built of flint, and its tall spire rises above the pine woods which surround it. I wonder how many visitors to the Church have heard the story of the staunch Methodist who built it. The Church was thoroughly restored by Earl Howe, in memory of his father, in 1900, at a cost of £1,000. King Edward VII worshipped here in January, 1902, when he was visiting Earl Howe.

It is a lovely tale, and probably a substantially true one, although like all the best family traditions, some of the details have become a little embellished. The 1820s would seem to fit the facts as we know them, not long after Lord Howe inherited the estate and was made an Earl, although the war with France was over by then and the Wesleyan Methodist chapel in Penn long since built. The Posse Comitatus of 1798 shows four Garlands, James Snr, James Jnr, Thomas and William, all carpenters and George Shrimpton as the steward. The 1841 census shows Charles Garland, a carpenter, aged 55, with a 40 year old wife, Sarah ( and a boy of 20. They lived opposite Slades Garage, in a cottage now called ‘Cobblers’, which he built himself.[] The uncle who had been vicar for some years, could have been the Rev Benjamin Anderson (Holy Trinity, Penn, 1808-13) , who seems to have lived in the parish before becoming vicar. Charles Garland died in 1846 so may well have been involved in the planning of the church which was consecrated in 1849. His widow continued his flourishing carpentry business with 5 employees in 1851. She died in 1859.

Miles Green: c.1990